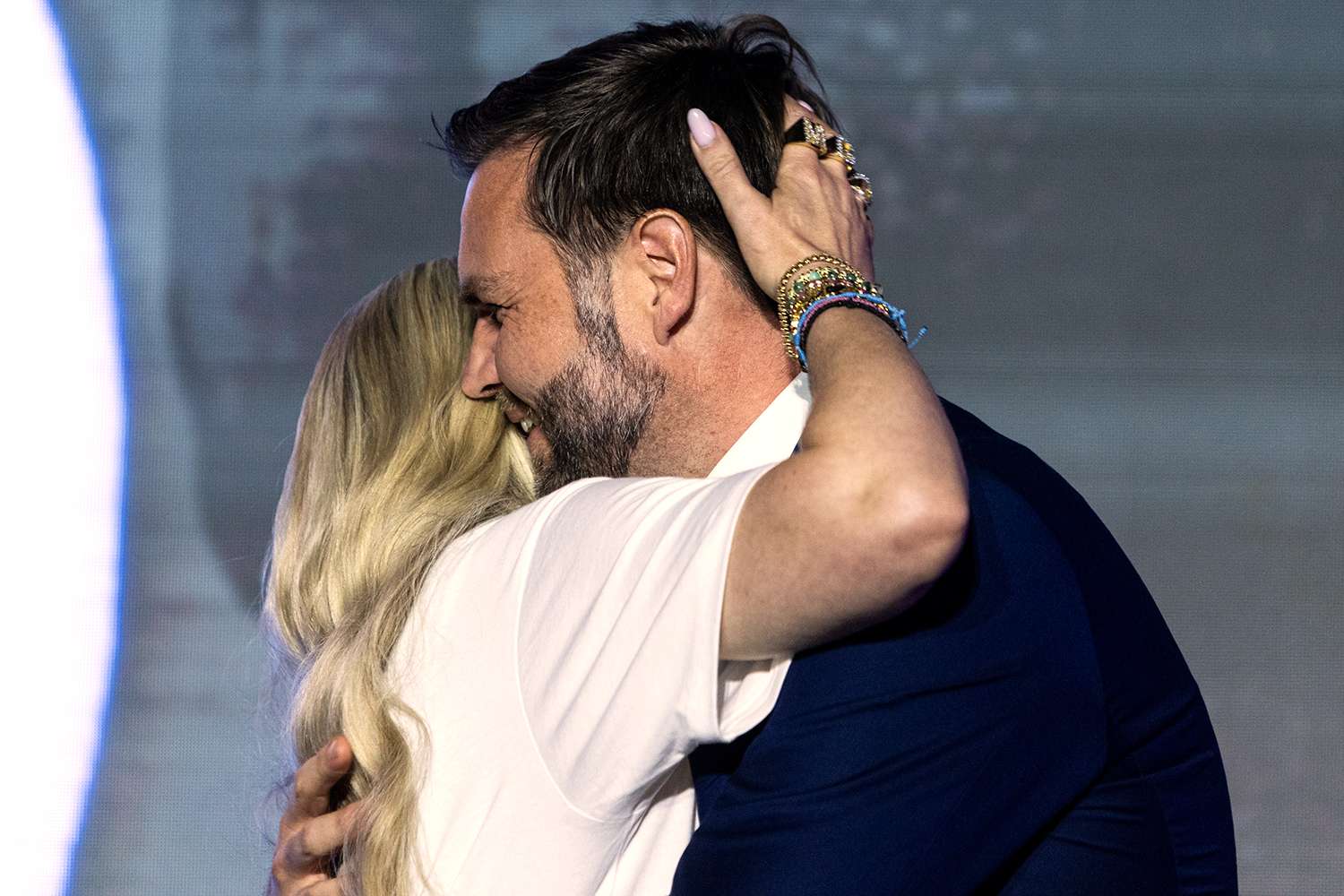

I read Hillbilly Elegy on a whim after becoming momentarily fascinated by JD Vance. The spark came from a press event where he was photographed mid-embrace with Charlie Kirk’s widow. The picture, taken without context, could have passed as innocent—an attractive blonde held naturally at the waist by a handsome, young man. But her hand changed everything: fingers sliding up his cheek, threading through the feathered wisps of his hair as if something intimate were unfolding.

People swore there was longing in that gesture, that it couldn’t possibly be innocent—especially given her introduction of him as the man who reminded her most of her husband, who had just been assassinated by a 22-year-old boy with a bolt-action rifle from 200 yards away. A boy, notably, with no real military background, unless you count a single family-vacation photo of him cheerfully handling an assault rifle with his parents.

Of course the insinuation is: the widow is on the hunt because she has to keep paying the bills. That JD Vance, married to an Indian woman named Usha, whom he met at Yale, before he wrote The Hillbilly Elegy, a damning memoir of his Appalachian background, really wanted to marry a white woman, now that he is funded by evil billionaire Peter Thiel, who in an interview, struggled to deny his desire to end the human race, which is very concerning indeed, considering he owns our generation’s version of the Death Star through Palantir.

I was fascinated by JD Vance because through all accounts, before his campaign was funded by Peter Thiel in 2023, “Jaydot” as one of his hillbilly uncles used to call him, stood for the opposite of what he represents now. His memoir had been widely praised for illuminating the unrepresented poverty of Appalachia—a population I hadn’t even known existed until I encountered his book.

The term redneck itself gained political potency after miners in the 1921 Battle of Blair Mountain tied red bandanas around their necks in solidarity as they fought for workers’ rights. It was once a badge of working-class identity and rebellion against corrupt systems. Decades later, that symbol of solidarity somehow morphed into a slur.

Before I read the book, I was captivated by this shift: how someone could, in three years and for an undisclosed amount of money, publicly abandon everything he claimed to believe in. And what of Usha—how must she feel watching her husband transform into someone unrecognizable? How does one become someone else entirely? Is money really that persuasive? And if so, how much does a soul cost?

But I finished Hillbilly Elegy, and as all layers reveal once peeled, what emerged was not a complex sociological memoir but an alt-right propaganda mouthpiece. Vance scolds SNAP recipients for buying frozen and canned food instead of fresh produce, like the “responsible” non-SNAP users he idealizes—ignoring that fresh food spoils quickly, costs more, and requires prep time that overworked people simply don’t have. From there he pivots into prescriptions for ending poverty: go to church, stay married, and get the hell out of dying industrial towns.

I’m oversimplifying, of course—but only because it’s difficult to write a well-developed critique while minding a toddler, typing with one hand, and wrestling with them using the other. And because I got both the flu shot and COVID vaccine in that same arm, it feels like I’m restraining my toddler with an amputated phantom limb.

What unsettles me most is how celebrated the book once was—by Republicans and Democrats. One of my favourite political commentators even called Vance “woke” during that period, despite Vance already working for Thiel’s VC firm. I have no doubt many of the Democrats who once praised the memoir can now see it for what it was: the prop that launched Vance’s political career. And with each new development, I become more convinced that the goal was always to place Vance at the top—Thiel as the final puppeteer.

I’ve often wondered why my mother, who literally clawed her way out of the slums, was always the first to condemn the poor as lazy. Her sisters would tell me how she used to study on the roof because the house—barely held together with corrugated tin and leftover lumber—was too loud for concentration, being the youngest of thirteen siblings.

My earliest memory of her is of her fingers twitching at night, as though strumming invisible guitar strings, her hands still typing in her dreams because they never stopped working when she was awake. And because she had made it, she believed anyone could. She didn’t see how impossible upward mobility is for most, let alone within a single generation.

My mother warned me never to give – never to offer anything for free, something that is bought, especially to those who beg, to those who have nothing and choose to ask instead, from other fellow human beings.

It’s a trick, she tells me, they will take and take, and they will present as a thing you feel sorry for, so that you are tricked into giving what is rightfully yours through your hard-earned, honest work. Never give, she says, never give away something for free, when you had to buy it for yourself.

Always one to test her, I ended up giving the rest of my Slurpee to one street kid who asked for it. Within seconds, my friends and I were swarmed, disfigured kids with shredded, lumps of flesh where their eyes used to be (The story goes that these disfigurements are perpetrated by their “pimps” – men/women who are either their parents or most likely, their abductors – or simply persons to whom they were sold to – to make the kids seem more pitiful, the more disfigured, the better – the younger and more disfigured, the better – and so on, as much as your heart can bear it, it does go on), palms outstretched, one kid after the next popping out of thin air just to appear beside my friends and I, to the point where we found ourselves raising our hands above the throng of begging flesh, encircled and encroached upon, trying to keep distance but failing, until my guardian/caregiver (the man who ended up grooming me) plucked my friends and I out of the throng and slammed us back into the white Lancer we came out of.

And so it seemed true – my mother’s warnings about the poor – how they can not only be lazy, but also dangerous. Bred to be aggressive from such an early age, who knew what kind of people they would turn out to be?

But then I blinked, and suddenly, I too, was homeless, in one of the richest countries in the world. I was neither lazy or dangerous.

In fact, I was going to University of Toronto and working a part-time job at a mirror store. Yet I was taking showers at the gym, sleeping at the storage room of the store, and spending all my free time either at work or at the library.

And all that time, while I sat in class and looked at my peers, while I helped yet another rich lady decide which frame fit her 5mm beveled mirror in her ultra-modern bathroom where everything from the shower handle to the hinges that allowed her 10 mm tempered, semi-opaque glass shower to swing smoothly and noiselessly was finished in the shiniest chrome you could imagine, I realized that the only difference between them and I, was this:

they had a private place to exist, and I had to live my entire life in public.

Just four walls to call your own—that’s the only difference.

for #NanoPoblano2025

NanoPoblano is the world’s least official November blog challenge. Participants and supporters are called Cheer Peppers. The BIG goal is 30 posts in 30 days. You can share your goal and your progress and your posts on the Facebook group at: https://www.facebook.com/groups/1336744293025187/

Leave a Reply